The Structure of Scientific Revolution, by T.S. Kuhn

Human beings find names essential. Names are discriminating; they distinguish one thing from another. By distinguishing one object from another object, we are aided in understanding the world. If we did not know the nature of an object to which we have given a specific name, it could not be distinguished from another object. Therefore, discrimination is essential to understanding objects. But names are not everything.

Another unique aspect of human beings is this: people by nature manufacture all kinds of tools. Names are also tools. With names we handle objects. But inventing tools may lead to the "tyranny of tools." When tools become tyrannical, instead of our making use of them, they rebel against their inventors and take revenge. Then we are made tools of the tools we make. This strange process is especially noticeable in modern life. We invent many machines, which in turn control human affairs, our human life. Machines, especially in recent years, have inextricably entered our life. We try to adjust ourselves to the machines, because the machine refuses to obey our will once it's out of our hands.

In our intellectual processes, ideas can also be despotic, for we cannot always control the concepts we use. We invent or construct many ideas, many concepts. They are very useful to us in dealing with our life, but convenient ideas frequently control their inventors and become despotic. Scholars who invent ideas forget that they formulated them in order to handle realities for a specific purpose. Each science, whether it is called biology or psychology or astronomy, works with its own premises and its own hypotheses. Each science organizes the field it has chosen--whether it be stars, animals, fish, and so on---and works with those realities according to the conceptual scheme especially devised to study them for our understanding. In pursuing their theories and using their formulations, scientists sometimes find themselves in situations that cannot be explained by their concepts. Then, instead of dropping those ideas and trying to create new concepts so that the unexpected difficulties can be included and handled, they often stick to the first ideas that they devised and try to make the new realities obey those ideas. Or they simply exclude anything which cannot be covered by the network of ideas they have created.

You might say that some scientists catch fish in a net with certain standardized meshes. Those fish that cannot be scooped up and captured in the net will be dropped--they won't be considered worth saving. The scientist-fishermen just take up those that can be caught in their net and try to explain their catch by means of the ideas they already possess. Other fish are considered not to exist. The person holding the net says, "These fish exist, caught in my net. All others don't exist...."

Such conclusions are altogether unwarranted. If scientists were content with reaching conclusions on what they can survey or measure, that would be all right. If they maintain that beyond that they do not know and don't venture any theory or hypothesis, that is also all right. But sometimes blinded by their own brilliance, by whatever success they have already achieved within certain boundaries, they try to extend that achievement beyond the established boundaries, as if they had already surveyed and measured that which is beyond what they already know. That is the trouble with some scientists.

Now the problem with ordinary people is that they blindly rely on what scientists say. But scientists must always make conditional statements, for they all begin with certain hypotheses. When scientists could not explain light, for example, they invented what they called "wave theory." But the wave theory did not account for all phenomena connected with light, so scientists introduced "quantum theory." This made the explanation of other phenomena possible, but then scientists discovered that in order to explain all phenomena they had to use both theories. Unfortunately, the two theories contradict each other, so that when the wave theory is adopted quantum theory must be thrown out. And when the quantum theory is utilized the other theory must be discarded. But certain phenomena exist, and scientists cannot deny their reality. Thus, however, contradictory they may be, both theories have to be adopted. Somehow they have to coexist.

Furthermore, we have the five senses, and our knowledge of reality is connected with them. If we had another sense, or two or three more senses beyond the existing five, we might find something altogether different existing. If we say that our five senses exhaust reality, that is presumptuous on our part. We can say, however, that as far as our five senses and our intellect are concerned, the world is to be understood, explained, and interpreted in a certain way. But there is no way to deny the existence of something (it may or may not be proper to speak of "someone") higher or deeper, something that covers the field more extensively. There may be something beyond the measure of our five senses and our intellect. We may possess some such thing in ourselves, perhaps largely under-developed. If we have another way of coming into contact with reality that is much deeper, more extensive, than our senses and intellect permit, it is presumptuous of us to deny such an intuition, and claim, "There is no such thing---nothing exists outside my senses and intellect."

~*~

Buddha of Infinite Light, by D.T. Suzuki

Images linked

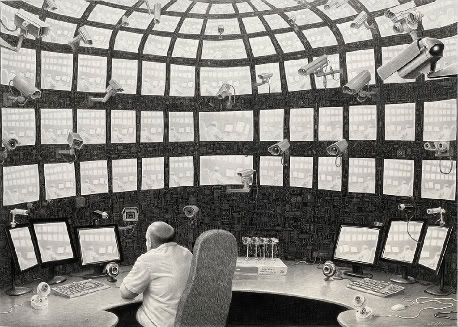

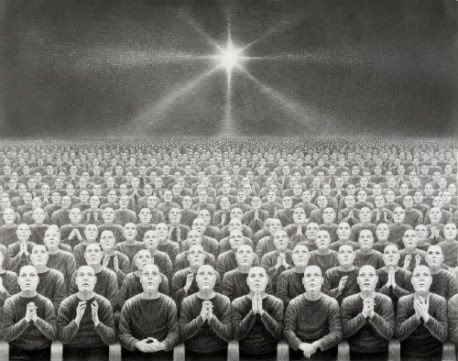

Art by Laurie Lipton

Programming by DPC

In order to KNOW, we must keep in mind the fact that reasoning and emotion, while indispensable as a foundation for our believing, can never give us that final, complete and everlasting inner “knowing” that for all our years dispels doubt as light dispels darkness. The light can come only from the high Self, for it is The Light.

This shining and wonderful thing which we are discussing has been the subject of numberless esoteric teachings and writings. They may all be summed up in the cryptic command, “Be still, and know that I am God.”

The intuitive knowing has been called “realization” in some lands. In Christian circles of a very early day it was called “illumination” because so many were able to see the High Self as a white light unlike any earthly light. Later on, the word “baptism” came to be substituted for “illumination” and the true meaning was gradually lost.

The early sages of Islam were inclined to veil the Secret less heavily. In the Kashf Al-Mahjub we can still read the final conclusion reached after long deliberation by a great sage whose bible was the Koran.

He wrote:

“You must know that the knowledge concerning the existence of the spirit is intuitive…, and the intelligence is unable to apprehend its (the spirit’s) nature.

Our search for God is our search for ourselves…..

Growing Into Light, by Max Freedom Long, pp. 59-60